A NEW VERSION OF THE SHOPHOUSE: A SOLUTION FOR LOW COST HOUSING

BACKGROUND

Back in 1995, not long after I set up my firm, I decided to focus on designing Low Cost housing. We did not have any clients yet, but I made a bet that the demand for such housing would always be present, and if the designs we came up with were good, then commissions would come. The bet came good: in the following years, the government embarked on a programme to get the public and private sector to build for the low-income.

Previously, private developers were mandated to build low-cost houses in their new housing estates. A minimum of 30% of their total number of units were to be houses priced below RM25,000. This proved to be a burden to developers and had limited output, so the rules were changed to encourage more building: In Johor for instance,the new requirement became:

- 20% low-cost RM25,000

- 10% low-medium type 1 RM60,00

- 10% low-medium type 2 RM80,000

The government entrusted a government owned corporation, TPPT Sdn Bhd, to work with the private sector and State governments to build low-cost housing. The mood of the times is reflected in the book produced by a think-thank which was closely allied to the government : "Low-Cost Housing - A Definitive Study". The problem of housing for the low income was going to be solved!

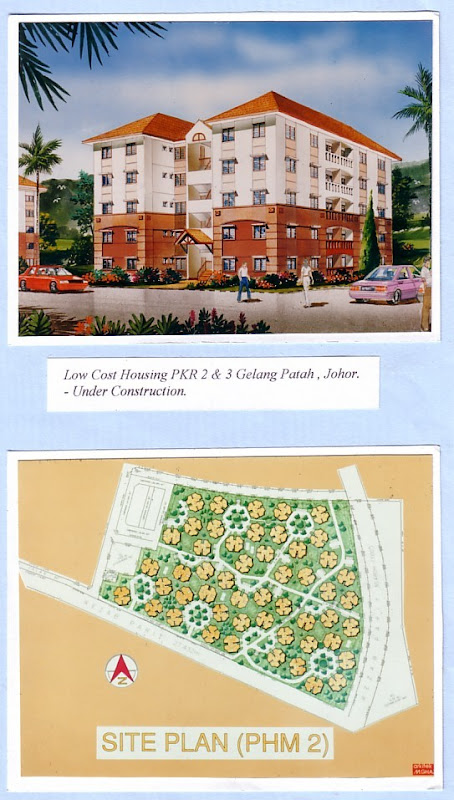

This provided an opportunity for Arkitek M Ghazali to introduce our ideas for "point blocks": ie 5 storey walk-up blocks with only 4 units to each floor accessible from a single staircase . We found that point blocks were economical: the ratio of saleable area to total area we were able to get was more than 95% , compared to about 85% achieved by the conventional slab blocks which could have up to 16 units per floor accessed from a central corridor.

These point blocks were arranged in a hexagonal formation (the first hint of honeycomb housing). In terms of land-use efficiency, we found this to be as efficient as the conventional rectilinear layout. In addition, the point block concept created "defensible spaces" and I instinctively felt that the clustering of the flats offered a much more community-friendly environment.

The recession of 1997/98 put a stop to the would be boom in low-cost housing.

However, the firm was able to see quite a few of its ideas come to fruition:

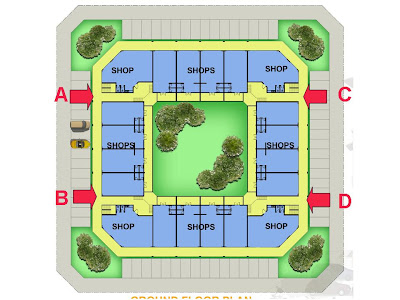

Octagonal low-cost 5 storey point-block flats, eight units on each floor, laid out in a hexagonal grid in Nusajaya, Johor

Medium-cost students 5 storey point-block apartments, four units to each floor, laid out in a hexagonal grid in Universiti Industri Selangor, Batang Berjuntai, Selangor

By the year 2000, Arkitek M Ghazali had started to work with Peter Davis of Universiti Putra Malaysia who was the top expert for Thermal Comfort. With this partnership, we shifted our focus from "Low-Cost Housing" to the concept of "Affordable Quality Housing". Specifically, this meant a retreat from the emphasis on cost, and looking more at quality.

By this time it was clear that the housing that came out from the current low-cost policy was not satisfactory. The construction cost of a low-cost house that met the minimum requirements was more then the selling price. Developers (or rather ordinary house purchasers) had to subsidize the low-cost housing; not surprisingly, developers designed and built them to minimum standards. Many of the new housing schemes looked likely to become slums. The low-cost housing were almost always segregated in the worst location of any development, away from shops, amenities and public transport. The were mainly 5 storey walk-up flats, about 60 units per acre, some with the ground floor empty, with only about one car parking space for every two units, crowded and all badly maintained.

It was expected that the low-income people would grab the chance at home ownership! But this was not the reception that was given. In the states of Johor and Selangor where there is the problem of property overhang, unsold low-cost houses made up the main component in the number of unsold completed properties. Resale values were often lower than the original purchase price. In many cases where the banks took over and tried to auction off the properties, there were few takers and reserve prices drifted lower and lower to ridiculous levels.

In our opinion, it was not so much the size or standard of the apartment units that is at fault (these are already generous), but rather the location and external enviroment. The low cost schemes are perceived as"low-cost flats for low-class people".

In one of our projects in Kajang, whilst the 5 storey mixed low-medium(750sf) and medium-cost(850) flats ranging from RM61,000 to RM80,000 sold out; yet just next door, the 6-storey low-cost flats(650sf), slightly smaller and with a lower quality of finish, were still only about 50% sold a year after completion.

The situation now is absurd! Developers make a loss from building low-cost houses even when they are able to sell all of them - when they remain unsold, their cashflow and profitability can become seriously compromised. But still, they are being forced to build low-cost house that they don't want to build, that the low-income people don't want to buy. Whilst the middle class buy houses that appreciate in value, the buyers of many low-cost flats, especially those out of town, have seen the value of their homes dwindle. Developers being generally smart, shift their focus to the high-end products which can more easily subsidize the 30% or 20% low-cost quota, which they build in less valuable outlying areas; or if they can help it, through delaying tactics and pleas for waiver, not build at all!

In my opinion, there should be a change in the government's policies that relate to housing . Still I am an architect not a politician, and the way that I choose to contribute is by suggesting how to plan, design and build housing for the low-income within the existing policies and regulations.